- Home

- Angel Sanchez

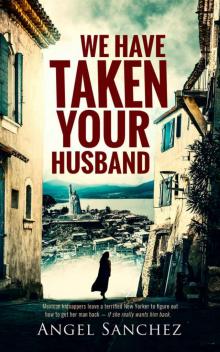

We Have Taken Your Husband

We Have Taken Your Husband Read online

We have taken your husband

By Angel Sanchez

The photo is of an ancient Indian woman on her knees, begging in the plaza, eyes closed, one hand extended, an icon of Mexican village life. It’s one in a series Ariana shot in the past month and is now editing on her laptop as she whiles away a rare evening alone. She fusses with the color saturation, loses interest, puts aside her laptop. Night has fallen over the village. She walks to the intricately carved cabinet beside the bookshelf and pours mezcal into a tall shot glass.

It’s nearly ten. Schuyler should be back by now.

She rubs a slice of lime around the rim, drops the rind into the glass, settles back in her chair. It’s one of those rustic chairs you see everywhere in Mexico: pigskin stretched over cedar slats. She tips back on its round base and pivots toward the window with its second-story view of clay-tiled rooftops and beyond them the huge old trees lining the village plaza, three blocks away.

The house — four bedrooms, four tiled baths — is otherwise inward looking. A central courtyard is flanked on both sides by porticos lined with massive wooden columns sheathed in bougainvillea. At the far end of the courtyard, four broad stone steps drop down to a high-walled garden with cobbled walkways, fruit trees, flower beds and clusters of bamboo that have grown too tall. There is a two-room casita out there, a little cottage that would be a maid’s quarters, if they had a full-time maid. Instead they have lots of guests.

Not bad at all, Ariana thinks to herself as she glances around the room and out across the roofs of the small mountain town that is Patzcuaro. Another sip of mezcal reinforces the snug, cozy feeling that comes with realizing how far away New York is and all the hassles and anxieties of her decades living and working there. No doubt about it: their Mexican retirement home is an upgrade on the rambling, overloaded apartments they had on the Upper West Side. The envy and admiration of friends who come down for visits is almost embarrassing, given the couple’s left/liberal politics. But for Schuyler, the Patzcuaro house isn’t a first experience of the seigneurial style. His father inherited one of those rambling estates along the Hudson River about a hundred miles north of the city and somehow managed to hang onto it into Schuyler’s early adolescence. It provided intermittent refuge during the breakdowns and illnesses that were an overture to his mother’s early death. And then, like her, Bairnwood was gone.

Ariana begins to feel a vague sense of irritation that Schuyler has not come back yet. She remembers the glass of mezcal on the table beside her. She wets her lips with it, then thinks better of nursing it slowly. The swig flows like lava over her lungs, her heart, her stomach. It brings on an involuntary shudder of satisfaction. When she hears Schuyler at the door, fresh back from his AA meeting, she will slip the glass under the chair. For now, she will enjoy mezcal immensely.

Schuyler has begun to mention her drinking as he deals with his own. Ariana is not in the least tipsy, but she will know better than to argue with him if he starts in on her this evening, there being no conversation more pointless — as both of them know — than arguing with a cold-sober spouse, fresh back from an AA meeting, about whether you’re drinking too much.

Schuyler connected with AA three months ago — or reconnected. He had given it a try back in the ‘90s in New York. Ariana really didn’t think his drinking was all that excessive, but kept her mouth shut. What else would he expect a spousal souse to say. “You’re fine, dear. Have another.” Schuyler got back into AA here in Patzcuaro at least in part for ulterior reasons. Sobriety aside, it’s a setting where he is forced to speak Spanish. And there is the welcome possibility of getting to know more Mexicans — real Mexicans, not just the ones who knock up against the edges of the expat colony.

A guilty pleasure: In his absence, Ariana has taken to thumbing through Schuyler’s notebooks. If she asked his permission, it’s likely he would say, “Fine. Go ahead.” It is equally likely he would say, “No. Please don’t. If I ever finish what I’m working on, you’ll be the first to see it.”

Which is why she hasn’t asked.

Not that his notebooks are any kind of secret. They occupy a linear yard of bookcase shelving and are in plain view. And he is, after all, her husband. They are exempt from testifying against each other in court. Isn’t there a parallel privilege that allows her access to a husband’s notebooks?

The individual entries are not dated, as they would be in a proper diary. And for good reason: Schuyler jumps all over the place. Childhood memories are interspersed with yesterday’s reflections on sex and people. He writes in the first person; he writes in the third. Now and then, as is fashionable, Ariana sees him trying out the second person: You do this, you do that; on a sun-washed afternoon in late November you wonder if …

Home alone, as she is on this occasion, Ariana’s custom, after an inch or two of mezcal or a toke of marijuana (just two), is to open a notebook at random and read whatever passage she lands on. It’s a bit like the I Ching, she has decided: an insight is provided — but in answer to a question she hasn’t thought to ask. Maybe the accidental selection is auspicious, prophetic: a glimpse of what may lie ahead, even if what she lands on is a glance back into the rabbit hole that is the past. This evening fate coughs up a passage that has a familiar ring to it. It takes her a few sentences to realize that Schuyler is retelling (and embellishing) an anecdote from her own childhood, something she must have told him.

A young girl just coming of age — named Elise but obviously Ariana — is walking her aged grandfather through the little zoo in Central Park on a Sunday afternoon:

The menagerie was a place where wild animals were cruelly confined and carefully protected, a kiddie-land delight that also exposed young visitors to rank odors and the sometimes shocking transgressions of chimpanzees in heat. That made it a psychological backdrop perfectly matched to the ambiguities of late adolescence. The caged animals were still interesting to Elise, but not more so than the uncaged wildlife: the balloon sellers, the fecund couples pushing baby carriages, the sketch artists, the small posses of street kids moving along the asphalt pathways in loose formation, scowling and talking loud, flicking ash, snatching up a stranger’s discarded, still smoldering cigarette butt and sucking a last few drags from it.

One day Elise and her grandfather had paused before a small folding table. It was covered with crystal goblets filled with water to varying levels. A young man rang music from the glasses by running a wet finger around their rims.

He was not much more than a teenager himself — but already a man, with black, black hair and thick eyebrows and a face shaved close, probably that morning, and yet dark with the stubble that would be a beard in less than a week, if he let it go.

She caught his eye, and he started showing off, lingering over one of the goblets longer and longer, scouring the rim with his finger, faster and faster, dipping his finger into the water to keep the sound pure and loud (louder!) until, to her astonishment, the goblet suddenly shattered. She flinched and he grinned up at her, shaking the finger as if it were cut or as you might shake it after touching a clothes iron you had forgot to switch off. Then, with a wink, he picked up the melody again, a song from which one note was now missing.

The unfinished anecdote runs on another page or two, but she puts down the notebook.

Still no sign of Schuyler. It irks her more than it worries her. It irks her that he isn’t back and it irks her that he has managed to irk her, because this is something they have talked about, and she is not supposed to care. We’re grownups, she has told him. She can look after herself. So can Schuyler. Their autonomy and independence — absolute, unquestioned — is something they insist on. No checking in just for the sake of checking in, a

t least not since Schuyler’s son grew up and parental responsibilities trailed off and then pretty much ended.

The bottle of mezcal winks at Ariana from the sideboard, and she pours another shot. She could be making something of the evening. Had she known Schuyler would be so late, she could have visited with friends; she could be tossing back a nightcap at the club that has opened near the basilica. Instead, she goes over to the sleeping area and switches on the television. The screen fills with one of those Mexican talent shows, at once idiotic and enigmatic. Contestants rush here and there in the performance of antic feats before a shrieking audience. She switches the channel: a TV reporter with dramatic eye makeup is doing her stand-up along a nighttime street. The camera cuts to the restaurant behind her, followed by a shot of a mob rubout worthy of Weegee. One of two corpses sprawls face-up on the floor. Its left leg and right arm are splayed crazily, a marionette tossed aside by a bored child. The other corpse has been thrown against the back of a chair, like a shrugged off overcoat. Ariana’s Spanish is not strong enough to pick up on the particulars, but she gets the gist from the few words she can cull from the newscaster’s rapidfire patter. “Execution-style … assumed to be the work of los Caballeros Templarios,” the newest of the cartels vying for supremacy in the state, Michoacan. She hears the name Apatzingan, a town closer to the Pacific that has been a hotbed of cartel violence.

And then this, an update on early stirrings as politicians begin jockeying to succeed Obama, now well into his second term: questions about Hillary Clinton’s high-priced speeches for Wall Street bankers, noise from New York real estate developer and television personality Donald Trump who vows to build a concrete wall across the border with Mexico. But no one takes his candidacy seriously, the newscaster opines, least of all his vow to somehow make Mexico pay for such a wall. Even his son-in-law dismisses Trump’s chatter as nothing more than a bid to raise his profile ahead of contract negotiations aimed at jacking up faded ratings for “Celebrity Apprentice.” Finally, a continuing story out of Cheran, a small town just over the ridge from Patzcuaro. Indigenous women lying in the roadway have again blocked trucks engaged in illegal logging on tribal land — a flare-up of something that appeared to have been halted two years ago. Their goal is to shame federal authority into (again) cracking down on the logging cartel. The TV footage shows a stopped truck and a Purépecha woman being loaded into an ambulance. It is unclear to Ariana whether she is dead or alive.

She flicks off the TV. The violence can seem ubiquitous and yet she has never seen or felt it personally.

Patzcuaro’s police chief was beheaded a year or so ago. A month later, the federal police substation was strafed (one dead, one injured: a gesture, rather than a serious assault). The gunmen were assumed to be sicarios. The substation stood — still stands — at the foot of Avenida Lazaro Cardenas, a few blocks from the embarcadero, where the lanchas pull out into weed-choked water and make for the inhabited islands: Janitzio, Pacanda, Yunuen. Schuyler pointed out the substation, the last time they drove by. The bullet holes were no longer visible. The concrete had been smoothed and the insignia of los federales repainted.

Over morning coffee in the Plaza Grande, the expats cling to optimism. They buck each other up by wondering aloud if they might be immunized against cartel attacks. “We’re too much trouble,” someone says, settling his cup in its saucer and then, with a wink, knocking on wood.

“The gringos have the money,” someone says, speaking as though they are not gringos themselves. “The cartels are interested in money, but they are more interested in power. They don’t want the trouble that comes with one of us: the FBI, the DEA. Our dollars are a lure, but they are also a shield.”

“Maybe you better ask Alyssa Quigley about that,” someone mutters. Alyssa and Mo lived in Patzcuaro before finding their way to San Miguel de Allende, the Valhalla of haute bourgeois expatriation, a pricier town than Patzcuaro. Mo (for Morgan) is one of a very few Americans — State Department hysteria to the contrary — who have actually fallen prey to the cartels in recent years. At least everyone assumes a narco was behind Mo’s demise. No matter that Alyssa paid a seven-figure ransom, her husband’s body turned up three weeks later in a barranca — a ravine — west of Mexico City. The corpse appeared to have been mutilated even before the rats and ravens got to it.

Not all upper lips are stiff, however.

There is a British couple with a seasonal allegiance to Patzcuaro, she of Jamaican heritage, he Irish, both born in London. They have two cute kids, plenty of money. (He is with one of the big beverage companies: Smirnoff, Pepsi, one of those.) They have been living in Mexico City but have put in for a transfer: New York or maybe back to Bogota, where they lived for a time when the kids were infants, a city with its own eruptions of violence but with tall apartment towers and more reliable security. They make no secret of the growing temptation to take to their heels. This skittishness embarrasses them, but, as they say: “You don’t have little kids to worry about.”

The Brits — Cassandra and Ian — move on out of earshot. “Oh, they never really liked Patzcuaro. They don’t really fit in here,” someone says.

Others defect incrementally, stage by stage. Seasonal visitors delay their annual arrival or leave a bit earlier than the year before. There is talk of doing a house exchange with a lovely family they met the previous spring in Provence.

Late at night, Ariana and Schuyler uncouple and prepare for sleep. Now is a time to talk safety. “Look, Ariana. We are not glued here. I don’t see us getting our money out of this place, but we knew that was a risk going in. We could always dump it. Or we could rent it out. Hell, we could just button it up tight, go back to the states and wait a few years to see if Mexico gets its shit together.”

Schuyler is implying that the choice is Ariana’s, in case she is weakening in her resolve to tough it out. In fact, she is hoping he’ll make the choice for them both, and would probably not be sorry if he said it was time to go.

But that would not be Schuyler. The violence is the Mexicans’ problem, he believes, but the expat community has an obligation: “We owe it to our Mexican friends to stand with them, to bear witness to their ordeal.” And then there are statistics, and there is no arguing with the numbers: “The cartels? We are as likely to catch a stray bullet walking out of Vince and Mary’s place in the Quarter,” he says, mentioning friends they visit from time to time in New Orleans, one of the Stateside murder capitals . “I like it here. I am not going to run away.”

He rolls on his side and begins gently massaging Ariana’s back, as is their post-coital custom. And you know what: Jorge tells me it’s not even the cartels anymore. They have bigger interests: international cocaine smuggling, political extortion. The kidnappers are just street rats pretending to be with a cartel — or hoping they’ll hit the big time someday. Jorge told me that, and Jorge usually knows what he’s talking about.

Ariana showers and then wipes steam from the medicine-cabinet mirror. Behold! Ariana Altobelli naked, early fifties, still trim, still damn good looking, if she does say so herself. The auburn highlights in her thick black hair are only tinged with gray. Her face has lost some of the sharp angularity that TV loved, but the softening is offset by the eternal persistence of her Roman nose, the feature Al Hirschfeld dwelt on when the Times did its annual look at the current crop of network talking heads. (Schuyler has been known to say he married a toucan.)

She turns sideways. Her rose tattoo (left thigh), a youthful folly, is still concisely legible. By contrast, the coil of barbed wire that rings her husband’s bicep has begun to look like it was sketched on newsprint, crumpled in frustration by an unsatisfied artist, then, on second thought, smoothed out as best as possible.

She tries to imagine how she looks when no one is looking, not even her. No fetching smile allowed, no tightening the slightly slack skin below her chin, no flirting with memories of what she looked like in her youth.

Aging angers her. “I’ll give i

t all back eventually, of course, but why the hurry?” she thinks to herself. “Why the impatience? Ahead of the grave, why this obscene, slow-motion reneging on the gift of good health and the good looks that have been as inseparable a part of her as the celebrity TV gave her — minor celebrity, of course.

She remembers the notebook she had been reading and brings it with her to bed. She skips past the final pages of the story on the Central Park street musician and lingers over something quite different and rather offensive to her. Real? Imagined?

She has a thing about body odor. She is comfortable with it. Sometimes she asks me not to bathe for a couple of days, a whole week. Other times she wants me fresh from the shower. And there are body lotions and bath oils she asks me to use. Patchouli is an old favorite from her California days.

It depends on her mood, I guess, but I have never been very good at anticipating whether her mood is going to make her want me rank or sweet-smelling. Sweet is easy: a shower and a scent. Rank takes time and leaves me wishing it, too, could be bottled for instant application.

One time she said, I don’t know why anyone would want their lover to smell the same every time they had sex. This way it’s like I have a lot of lovers. Some stink. Some smell like soap. Some smell like girls.

We Have Taken Your Husband

We Have Taken Your Husband